Appendix

Auto-associative Memory

Auto-associative memories are content based memories which can recall a stored sequence when they are presented with a fragment or a noisy version of it. Firstly, using this, we dont have to have the entire pattern we want to retrive in order to retrive it. Secondly, auto-associative memory can be designed to store sequences of patterns, or temporal patterns. This feature is accomplished by adding a time delay to the feedback. With this delay, you can present an auto-associative memory with a sequence of patterns, similar to a melody, and it can remember the sequence. I might feed in the first few notes of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” and the memory returns the whole song.

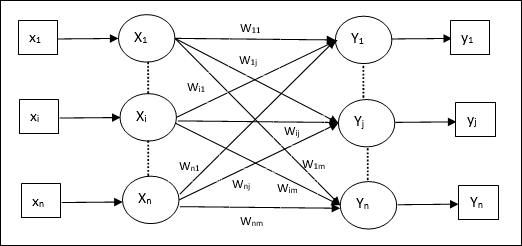

The simplest version of auto-associative memory is linear associator which is a 2-layer feed-forward fully connected neural network where the output is constructed in a single feed-forward computation.

All inputs are connected to all outputs via the connection weight matrix ‘W’ where each element of ‘W_ij’ denotes the strength of unidirectional connection from the ‘i’ input to the ‘j’ output. Since in auto-associative memories, we have x = y . Therefore, all stored sequences must be eigenvectors of matrix ‘W’. Assuming all stored sequences are orthogonal to each other, we can represent the weight matrix as W = XX^{-1} = XX^T, where X is orthonormal matrix of all stored sequences. Also, we are enforcing the weight matrix W to be symmetric so W_ij = W_ji. So, assuming we have ‘p’ sequences to store in our memory we can rewrite weight matrix as: W = sum_{i=1}^{p} x^i * x^i

Associated links:

http://cs229.stanford.edu/proj2013/Youssefi-AutoassociativeMemory.pdf

Chinese Room Experiment

Suppose you have a room with a slot in one wall, and inside is an English-speaking person sitting at a desk. He has a big book of instructions and all the pencils and scratch paper he could ever need. Flipping through the book, he sees that the instructions, written in English, dictate ways to manipulate, sort, and compare Chinese characters. Mind you, the directions say nothing about the meanings of the Chinese characters; they only deal with how the characters are to be copied, erased, reordered, transcribed, and so forth.

Someone outside the room slips a piece of paper through the slot. On it is written a story and questions about the story, all in Chinese. The man inside doesn’t speak or read a word of Chinese, but he picks up the paper and goes to work with the rulebook. He toils and toils, rotely following the instructions in the book. At times the instructions tell him to write characters on scrap paper, and at other times to move and erase characters. Applying rule after rule, writing and erasing characters, the man works until the book’s instructions tell him he is done. When he is finished at last he has written a new page of characters, which unbeknownst to him are the answers to the questions. The book tells him to pass his paper back through the slot. He does it, and wonders what this whole tedious exercise has been about.

Outside, a Chinese speaker reads the page. The answers are all correct, she notes— even insightful. If she is asked whether those answers came from an intelligent mind that had understood the story, she will definitely say yes. But can she be right? Who understood the story? It wasn’t the fellow inside, certainly; he is ignorant of Chinese and has no idea what the story was about. It wasn’t the book, which is just, well, a book, sitting inertly on the writing desk amid piles of paper. So where did the understanding occur? Searle’s answer is that no understanding did occur; it was just a bunch of mindless page flipping and pencil scratching. And now the bait-and-switch: the Chinese Room is exactly analogous to a digital computer. The person is the CPU, mindlessly executing instructions, the book is the software program feeding instructions to the CPU, and the scratch paper is the memory. Thus, no matter how cleverly a computer is designed to simulate intelligence by producing the same behavior as a human, it has no understanding and it is not intelligent. (Searle made it clear he didn’t know what intelligence is; he was only saying that whatever it is, computers don’t have it.)

Cocktail Party Problem

This is the task of attending to one speaker among several competing speakers and being able to switch the attention from one speaker to another at any given time.

Hebbian Learning

It was introduced by Donald Hebb in his 1949 book The Organization of Behavior.[1] The theory is also called Hebb’s rule, Hebb’s postulate, and cell assembly theory. Hebb states it as follows:

Let us assume that the persistence or repetition of a reverberatory activity (or “trace”) tends to induce lasting cellular changes that add to its stability. … When an axon of cell A is near enough to excite a cell B and repeatedly or persistently takes part in firing it, some growth process or metabolic change takes place in one or both cells such that A’s efficiency, as one of the cells firing B, is increased.

The theory is often summarized as “Cells that fire together wire together.”

The repeated stimulus of weak connections between neurons leads to their incremental strengthening. There is another type of inhibitory connection, that have an opposite response to a stimulus. Here, the connection strength decreases with repeated or simultaneous stimuli.

Turing Test

If a computer can fool a human interrogator into thinking that it too is a person, then by definition the computer must be intelligent.

Universal Turing Machine

Alan Turing conceived an imaginary machine with three essential parts: a processing box, a paper tape, and a device that reads and writes marks on the tape as it moves back and forth. The tape was for storing information— like the famous 1’s and 0’s of computer code (this was before the invention of memory chips or the disk drive, so Turing imagined paper tape for storage). The box, which today we call a central processing unit (CPU), follows a set of fixed rules for reading and editing the information on the tape. Turing proved, mathematically, that if you choose the right set of rules for the CPU and give it an indefinitely long tape to work with, it can perform any definable set of operations in the universe. It would be one of many equivalent machines now called Universal Turing Machines. Whether the problem is to compute square roots, calculate ballistic trajectories, play games, edit pictures, or reconcile bank transactions, it is all 1’s and 0’s underneath, and any Turing Machine can be programmed to handle it. Information processing is information processing is information processing. All digital computers are logically equivalent.